The United States Mint has produced its final penny, concluding more than two centuries of continuous one-cent coin manufacturing in a decision driven by economic reality rather than legislative mandate. The phase-out represents a significant milestone in American monetary history, though the transition’s gradual nature means pennies will remain a familiar presence in commerce for years to come.

The decision to cease penny production stems from a fundamental economic problem that has plagued the denomination for years: the cost of manufacturing each coin substantially exceeds its face value. In 2024, producing a single penny cost 3.69 cents, creating a 269% cost-to-value ratio that generated $85 million in annual losses for the Treasury.

This economic absurdity, whilst long recognised by monetary policy experts and economists who have advocated for penny elimination for decades, finally prompted action as the cumulative losses and the coin’s diminished utility in modern commerce made continued production indefensible. The Mint placed its final order of penny blanks in May, with production scheduled to conclude by early 2026.

The decision to halt production whilst maintaining the penny’s legal tender status creates a unique transition period where existing coins remain valid currency but no new pennies enter circulation. This approach avoids the logistical complications and potential public backlash that would accompany forced demonetisation or mandatory coin exchanges, instead allowing natural attrition to gradually reduce penny prevalence over time.

The 114 billion pennies already in circulation represent an enormous stockpile accumulated over decades of production. This vast inventory, distributed across households, businesses, banks, and various containers ranging from piggy banks to car cup holders, means most Americans will continue encountering pennies regularly for years despite production cessation. The coins tucked away in forgotten locations, wedged between sofa cushions, or deposited in wishing wells will slowly leak back into commerce or remain permanently lost.

The penny’s history stretches back to 1792 when the United States Mint opened and began producing large copper coins featuring Lady Liberty. These early pennies bore little resemblance to the modern Lincoln cent, measuring substantially larger and composed of different metal compositions that evolved as copper prices fluctuated and wartime needs demanded material conservation.

The coin’s most recognisable feature, President Abraham Lincoln’s profile on the obverse side, was added in 1909 to commemorate his 100th birthday. This design choice marked the first time a historical figure appeared on regular-issue United States coinage, breaking from the allegorical representations that had dominated American coins since the nation’s founding.

The reverse side has undergone several transformations reflecting changing artistic preferences and commemorative purposes. The original wheat stalks design gave way to the Lincoln Memorial, which in turn was replaced in 2010 by the Union Shield, a symbol chosen to represent Lincoln’s preservation of the Union during the Civil War.

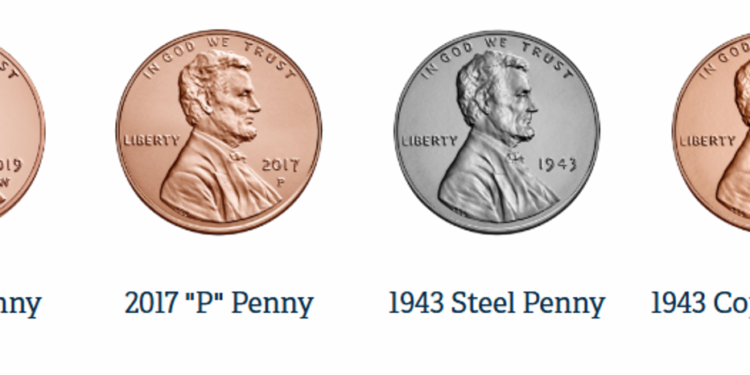

The penny experienced notable variations throughout its production history. During World War II, steel pennies were struck to conserve copper for military applications, creating collectible anomalies that remain sought after by numismatists. In 2017, a special “P” mint mark appeared on pennies from the Philadelphia Mint to commemorate the facility’s 225th anniversary. The West Point Mint produced a limited collectible run in 2019, further diversifying the coin’s variations.

The production cessation creates immediate practical challenges for retailers and financial institutions that lack federal guidance on managing the transition. Banks report that coin-order terminals are limiting penny shipments, whilst the Federal Reserve has indicated future penny distribution will occur only “as inventory allows,” a vague commitment that provides little certainty for businesses planning their cash-handling operations.

Retailers are experiencing penny shortages that affect their ability to make exact change, forcing adaptations that include requesting exact payment from customers, rationing remaining penny supplies, or offering promotions designed to eliminate small change requirements. Some convenience stores have already implemented these measures, creating inconsistent customer experiences depending on which establishments have depleted their penny reserves.

The eventual depletion of penny supplies will likely necessitate price rounding to the nearest nickel for cash transactions, following practices adopted by other countries that have eliminated their smallest denominations. Canada, Australia, and several European nations have successfully implemented such systems without significant disruption, though the transition required consumer education and business adaptation.