Creating a virtual brain may sound like science fiction, but for neuroscientists at Seattle’s Allen Institute and their collaborators in Japan, it represents a monumental achievement toward understanding brain function at the most fundamental cellular level, with potential implications for treating neurological diseases and unlocking the mysteries of consciousness.

Researchers announced this week they have successfully simulated the entire cortex of a mouse brain, encompassing nearly 10 million neurons connected by 26 billion synapses, using one of the world’s fastest supercomputers in what represents the most comprehensive and detailed brain simulation ever achieved.

“This shows the door is open,” Allen Institute investigator Anton Arkhipov stated. “It’s a technical milestone giving us confidence that much larger models are not only possible, but achievable with precision and scale.”

Arkhipov and his colleagues presented their groundbreaking work this week in St. Louis during the SC25 conference on high-performance computing, describing how they created a simulation that models the activity of an entire mouse cortex with unprecedented detail and accuracy.

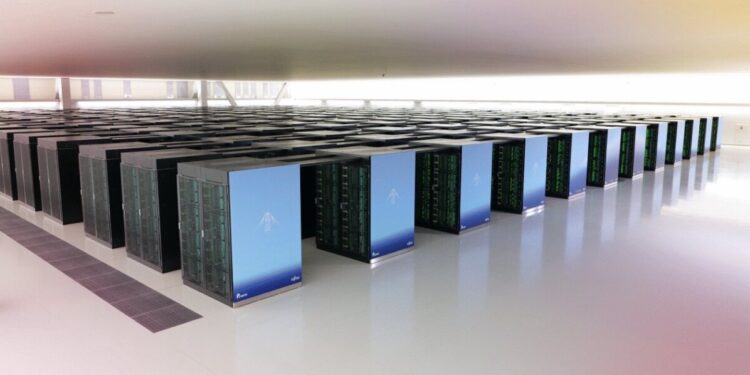

The achievement required combining vast datasets from the Allen Cell Types Database and the Allen Connectivity Atlas with the immense computational power of Supercomputer Fugaku, a computing cluster developed by Fujitsu and Japan’s RIKEN Centre for Computational Science. Fugaku is capable of executing more than 400 quadrillion operations per second, or 400 petaflops, making it one of the most powerful computing systems in the world.

The research team translated the massive biological dataset into a three-dimensional model using the Allen Institute’s Brain Modeling ToolKit, a sophisticated software framework designed to represent the complex architecture of neural tissue. A simulation programme called Neulite then brought the data to life, creating virtual neurons that interact with each other in ways that mirror the electrochemical signalling occurring in living brain cells.

Scientists executed the programme in different scenarios to test its capabilities and validate its accuracy, culminating in an experiment that used Fugaku’s full-scale configuration to model the entire mouse cortex simultaneously.

“In our simulation, each neuron is modelled as a large tree of interacting compartments, hundreds of compartments per neuron,” Arkhipov explained. “That is, we are capturing some sub-cellular structures and dynamics within each neuron.” This level of detail far exceeds previous brain simulations that treated neurons as single points or simple structures, allowing researchers to model the complex internal dynamics that determine how neurons process and transmit information.

During the full-scale simulation, the system required no more than 32 seconds to simulate one second of real-time activity in a living mouse brain. “This level of performance, 32 times slower than real time, is quite impressive for a system of this size and complexity,” Arkhipov stated. “It is not uncommon to see a factor of thousands of times slower for such very detailed simulations even much smaller than ours.” The relatively modest slowdown compared to biological time represents a remarkable achievement given the computational complexity of modelling billions of synaptic connections and the intricate dynamics within millions of neurons.

The researchers acknowledge that substantial additional work is needed to transform their simulation from a technical demonstration into a tool capable of modelling neurological diseases or testing therapeutic interventions. The current model lacks several critical features of biological brains that would be necessary for such applications.

Most notably, the simulation does not incorporate brain plasticity, the phenomenon by which neural connections strengthen, weaken, form, or dissolve in response to experience and learning. Plasticity underlies memory formation, skill acquisition, and recovery from brain injury, making it essential for understanding many neurological conditions and potential treatments.

“If we want to mention something specific besides plasticity, then one aspect that is missing is the effects of neuromodulators, and the other is that we currently do not have a very detailed representation of sensory inputs in our whole-cortex simulations,” Arkhipov stated. Neuromodulators are chemicals like dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine that broadly influence neural activity and play crucial roles in mood, attention, motivation, and numerous brain functions relevant to psychiatric and neurological disorders.

“For all of these, we need much more experimental data than currently available to make much better models, although some approximations or hypotheses could be implemented and tested now that we have a working whole-cortex simulation,” he added, suggesting that even the current incomplete model provides a platform for testing ideas about brain function that were previously impossible to explore.

Arkhipov indicated the project’s ultimate goal extends beyond the cortex to simulate an entire brain. “There’s a distinction between whole-cortex and whole-brain,” he pointed out. “The mouse cortex and our model of it contains about 10 million neurons, whereas the whole mouse brain contains about 70 million neurons.” The remaining 60 million neurons reside in subcortical structures including the thalamus, hippocampus, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and brainstem, all of which perform essential functions and interact extensively with the cortex.

A human brain simulation would require an even greater computational leap. The human cortex alone contains not 10 million neurons but 21 billion, representing a 2,100-fold increase in scale compared to the mouse cortex model. The complete human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons, each potentially connected to thousands of others through hundreds of trillions of synapses.