The White House took the extraordinary step of designating fentanyl as a weapon of mass destruction this week, a classification traditionally reserved for nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, as President Donald Trump escalates military operations against suspected drug traffickers.

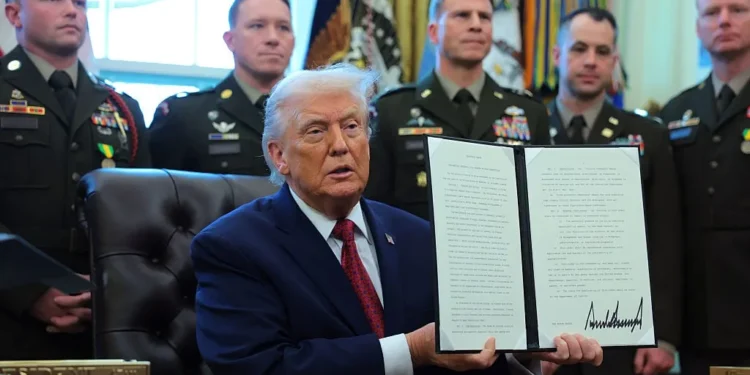

Trump signed an executive order formalizing the designation, which administration officials say reflects the deadly toll synthetic opioids have taken on American communities. More than 48,000 people died from fentanyl overdoses in 2024 alone, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The designation came as the U.S. military conducted strikes Monday against three boats in the eastern Pacific, killing eight people the administration described as narcoterrorists. These attacks represent part of at least 25 military operations targeting suspected drug trafficking vessels in recent months.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and Secretary of State Marco Rubio briefed members of Congress Tuesday about the expanding boat strike campaign, defending the use of military force against what they characterized as threats to American lives.

“To counter designated terrorist organizations, cartels, bringing weapons, weapons meaning drugs, to the American people and poisoning the American people for far too long. We’re proud of what we’re doing,” Hegseth told reporters after the classified briefing.

Trump has repeatedly blamed Venezuelan cartels for flooding America with fentanyl, calling drug traffickers a “direct military threat” to the country.

“These are a direct military threat to our country. They’re trying to drug out our country,” Trump said Monday while announcing the latest strikes.

But drug policy experts and law enforcement data tell a different story. Virtually no fentanyl comes from Venezuela. The synthetic opioid is overwhelmingly produced in clandestine laboratories in Mexico using precursor chemicals shipped from Asia, particularly China.

Mexican cartels, especially the powerful Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco New Generation Cartel, control the production and trafficking networks that move fentanyl across the southern border. These organizations have built sophisticated operations that can produce the drug in massive quantities.

Dr. Jeffrey Singer, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute who studies drug policy, dismissed the weapon of mass destruction designation as political theater that won’t reduce overdose deaths.

“Calling it a weapon of mass destruction amounts to Orwellian newspeak, or maybe just gaslighting to create a moral panic, but it’s not gonna change anything,” Singer said. “It’s not gonna make illicitly smuggled fentanyl any more illegal than it already is, and it’s also not going to make the drug war any more winnable than it already isn’t.”

The classification raises questions about what practical effect it will have. Fentanyl trafficking is already a federal crime carrying severe penalties. The designation doesn’t automatically grant new legal authorities beyond what existing drug laws already provide.

What it does signal is the administration’s willingness to use military force against suspected traffickers, a dramatic expansion of the war on drugs that previous administrations avoided.

The military campaign has generated significant controversy, particularly over tactics employed during some operations. In September, military forces conducted what critics call a “double-tap” strike in the Caribbean. After an initial attack on a suspected drug boat, forces returned and struck again, killing survivors from the first attack.

Hegseth announced Tuesday that unedited video of the September incident will not be released to the public, though congressional committees will have access to review the footage in classified settings.

Some Republicans who attended the classified briefings expressed satisfaction with the legal justifications the administration provided for the strikes.

But Democratic lawmakers pushed back, demanding greater transparency and full public release of the video showing the September double-tap attack. Several members used the term “war crime” to describe the killing of survivors, arguing the tactic violates international humanitarian law governing armed conflict.

The double-tap controversy underscores the risks of militarizing drug interdiction. Rules of engagement designed for counterterrorism operations don’t necessarily translate to law enforcement actions against suspected criminals on the high seas.

The 25 operations conducted so far suggest the boat strike campaign will continue and potentially expand. But public health experts question whether sinking boats in the Pacific will meaningfully reduce the fentanyl supply flooding American communities.

The drug reaches the U.S. primarily through official ports of entry along the southern border, hidden in vehicles, commercial shipments, and among the millions of people and tons of cargo that cross legally each day. Small amounts of fentanyl go a long way because of the drug’s potency.

A kilogram of fentanyl can be pressed into thousands of counterfeit pills. Traffickers hide the drug in shoes, electronics, vehicle panels, and countless other concealment methods that make interdiction extraordinarily difficult.

The Venezuela focus appears driven more by geopolitics than drug trafficking realities. The Trump administration has taken an increasingly hostile stance toward the Maduro government, and framing fentanyl as a Venezuelan threat provides justification for potential military action.

But targeting the wrong country won’t solve the crisis. Mexican cartels will continue producing fentanyl as long as American demand persists and Chinese companies continue supplying precursor chemicals.

Singer and other public health advocates argue the focus should be on reducing demand through treatment, harm reduction, and addressing the despair that drives people to use drugs in the first place.

“You can’t arrest or bomb your way out of a drug crisis that’s fundamentally about unmet healthcare needs and economic desperation,” Singer said.

The 48,000 deaths in 2024 represent real people, real families torn apart by addiction and loss. Whether calling fentanyl a weapon of mass destruction and sinking boats in the Pacific will save any of those lives remains an open question.