Quint Manolovitz called his insurance agent with a simple question: does my renter’s policy cover the flood damage to my Pacific home?

The answer came back quickly. “Unfortunately, flooding is not covered. Theft, fire, everything but flooding.”

Ten days after a breach along the White River forced hundreds of residents to evacuate, Manolovitz and his neighbors are discovering what most Americans learn only after disaster strikes: standard insurance policies don’t cover floods.

Now the city of Pacific and King County Emergency Management are racing to secure financial assistance for recovery, urging homeowners, business owners, and renters to complete damage assessment forms that could unlock county, state, or federal aid.

Though nothing is guaranteed.

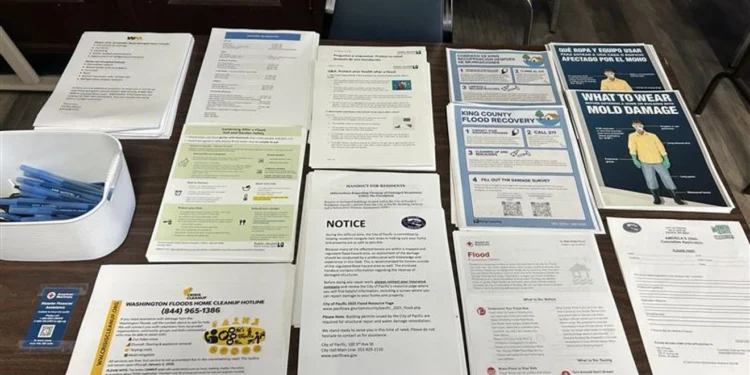

King County Emergency Management held an open house at Pacific City Hall on Friday where people could submit the forms in person and get their questions answered by officials who know the system.

Manolovitz lives near the HESCO barrier where the breach happened. Almost all the floodwater that swamped his neighbourhood has receded, but he’s still feeling the impacts.

“It’s cold,” Manolovitz said. “The ductwork is all flooded. Insulation under the house is all flooded, so I have some of those Amazon oil-filled space heaters.”

His home is one of 220 houses that city of Pacific officials say were damaged by the White River’s flooding at its peak.

“We do believe that all of those people have now been placed back in their homes, and they are in the process of cleanup,” explained Debbie Aubrey, a public information officer for the city. It’s a process that comes with a cost, she added.

Therefore, the city is urging impacted people to submit damage assessment forms to King County Emergency Management for the chance to secure financial assistance from the county, state, or federal government.

“We are a very small town. We have limited resources,” Aubrey continued. “So we will be relying on our partners, our county partners, and hopefully our federal partners, to help us with the recovery.”

Someone from the county’s emergency office explained that both Governor Bob Ferguson and King County Executive Girmay Zahilay have announced plans to designate recovery funds for impacted people. However, it’s still unknown if Washington state will receive federal monetary relief.

More than 200 damage assessment forms have been submitted across King County so far, and most people have reported that they do not have flood-specific insurance, according to King County Emergency Management.

This likely means financial support from elsewhere will be critical to hundreds of people locally.

“There are a lot of people who are going to need a lot of financial assistance to repair all the damage,” Manolovitz said whilst surveying his own neighbourhood’s destruction.

All impacted counties must submit their initial flood damage assessment numbers to the state by December 28, King County officials said. But King County will continue accepting completed damage assessment surveys after that date.

The insurance gap Manolovitz discovered represents a widespread problem in flood-prone areas across America. Standard homeowner and renter policies specifically exclude flood damage, requiring separate flood insurance policies that most people don’t purchase until after they’ve been flooded once.

The National Flood Insurance Program offers federally backed flood coverage, but only a fraction of at-risk properties carry these policies. In Pacific, a small city where flooding wasn’t considered a major threat until the White River breach, insurance penetration was likely minimal.

The damage assessment forms serve multiple purposes beyond just documenting losses. The data collected helps establish whether the disaster meets thresholds for federal emergency declarations, which unlock funding streams and programmes unavailable without that designation.

The December 28 deadline for submitting initial numbers to the state creates pressure on King County officials to gather as much data as possible quickly. Federal disaster declarations often hinge on demonstrating sufficient aggregate damage across affected areas.

Governor Ferguson and King County Executive Zahilay announcing plans to designate recovery funds provides some assurance that help is coming, but the amounts and eligibility requirements remain unclear. State and county funds typically provide smaller grants than federal programmes.

The 220 damaged houses in Pacific alone represent millions of dollars in repair costs. Flood damage affects everything from foundations to electrical systems to furnishings, with repair bills easily reaching tens of thousands per home.

Manolovitz’s flooded ductwork and insulation demonstrate how flood damage extends beyond what’s visible. Mould growing in wet insulation creates health hazards. Compromised ductwork reduces heating efficiency. These hidden damages drive up total repair costs.

The oil-filled space heaters Manolovitz bought from Amazon represent a temporary solution that costs money to operate every day. Winter electricity bills will climb whilst he waits for repairs or assistance.

Pacific’s small size and limited resources mean the city cannot fund recovery on its own. Cities collect tax revenue based on property values and sales activity. A city of Pacific’s size has annual budgets measured in millions, not the tens of millions needed for flood recovery.

The reliance on county and federal partners reflects how disaster response works in America. Local governments handle immediate response, but recovery requires resources only higher levels of government possess.